Fact Sheet

Understanding the Pennsylvania State Budget

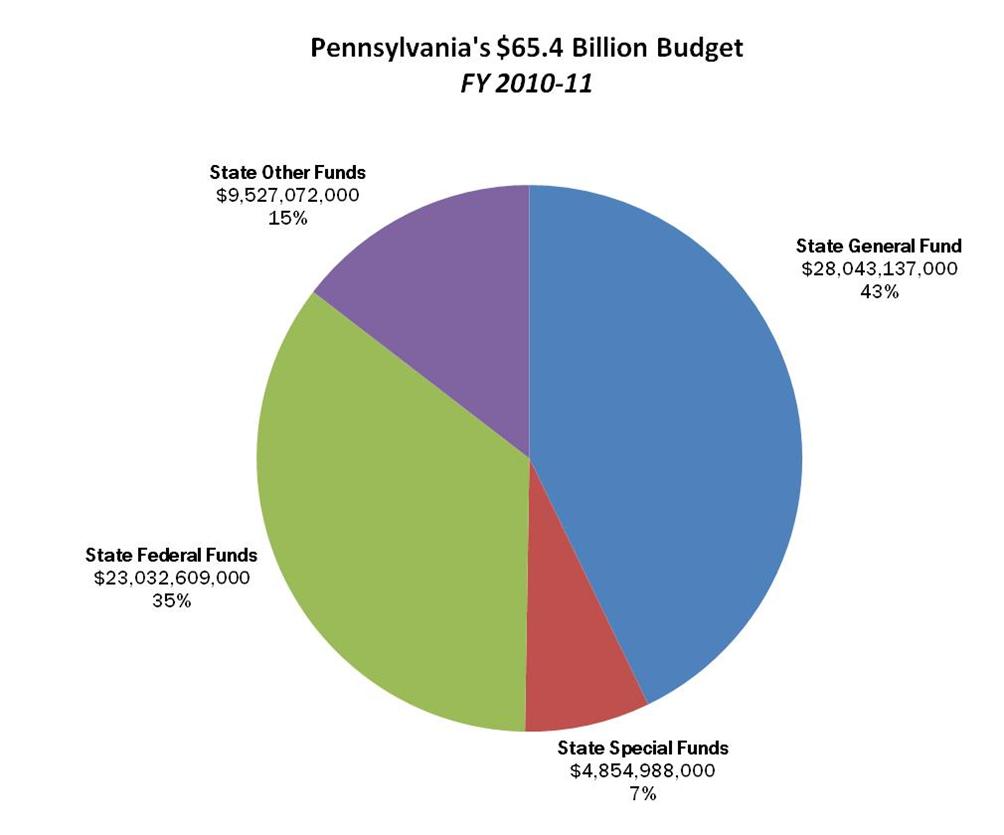

Introduction: Pennsylvania’s $65.4 Billion Budget

Pennsylvania’s total state operating budget for FY 2010-11 is approximately $65.4 billion—or $5,193 for every man, woman and child in the commonwealth. This policy brief looks at the entire state operating budget in order to give policymakers and interested citizens a better understanding of how Pennsylvania’s total operating budget is constructed in order to build a better one.

The General Fund (FY 2010-11) = $28.043 billion (enacted)1

The General Fund is comprised of monies that can be used for “general purposes,” as determined by the legislature and governor. All spending from the General Fund is voted on each year in legislation, which identifies the amount for each line item in the budget. The major General Fund revenue sources are the state personal income tax ($10.4 billion, 38%), most of the state sales tax ($8.6 billion, 31%), corporate income and other business taxes ($4.9 billion, 18%), cigarette and alcohol taxes ($1.4 billion, 5%), and inheritance taxes ($795 million, 3%).

The General Fund spending total for FY 2010-11 also includes $2.7 billion in one-time federal funds from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act and other “stimulus” monies.

Special Funds = $4.85 billion (estimated)2

There are 11 “special funds” in the Pennsylvania state operating budget. The largest of these are the Motor License Fund ($2.7 billion, 56%), which includes gasoline taxes and motorist fees, and primarily funds transportation-related projects and functions; the Lottery Fund ($1.6 billion, 33%), which primarily funds the Department of Aging; and the Tobacco Settlement Fund ($370 million, 8%), which involves payments from tobacco companies following a 1999 lawsuit.

Most, but not all, spending from these special funds is also voted on annually by lawmakers, and the line items are included in the General Appropriations Act. Spending from the Motor License Fund is restricted to “public highways and bridges” by Article VIII of the Pennsylvania Constitution. The remaining special funds were created by statute, either with limitations on their use (which can be changed by legislation) or with a general purpose for how the funds could be used.

Other Funds = $9.53 billion (estimated)3

There are 139 other funds included in the Pennsylvania state operating budget. Spending from these funds is generally not voted on annually, but set by formula. Many of these funds have funding streams linked closely to their purpose—such as the Unemployment Compensation Benefit Payment Fund and the Worker’s Compensation Security Fund. Some of the other funds were created to provide “dedicated funding” to certain programs. For example, the Public Transportation Trust Fund receives a portion of sales tax revenue (4.4% of receipts) to fund mass transit agencies; the Pennsylvania Race Horse Development Fund and the Pennsylvania Gaming Economic Development and Tourism Fund both get a portion of slot machine revenue to support their various programs. Other funds also include the State Stores Fund (liquor stores) and the MCare Fund (for medical malpractice premium subsidies).

Federal Funds = $23.03 billion (estimated)4

The Pennsylvania state operating budget also includes federal funds that are expended by the state. These funds come in several forms. Some are block grants, which allow the commonwealth some latitude in how the money is spent. Other funding comes for specific programs—either mandated by the federal government or optional for states—funded in part or totally by the federal grant, but administered by the state. Most of this funding comes in the form of matching payments for joint programs, primarily Medicaid (Medical Assistance), in which the federal government matches state government spending at a set formula.

This total does not include federal stimulus funds that were included as part of the General Fund Budget.

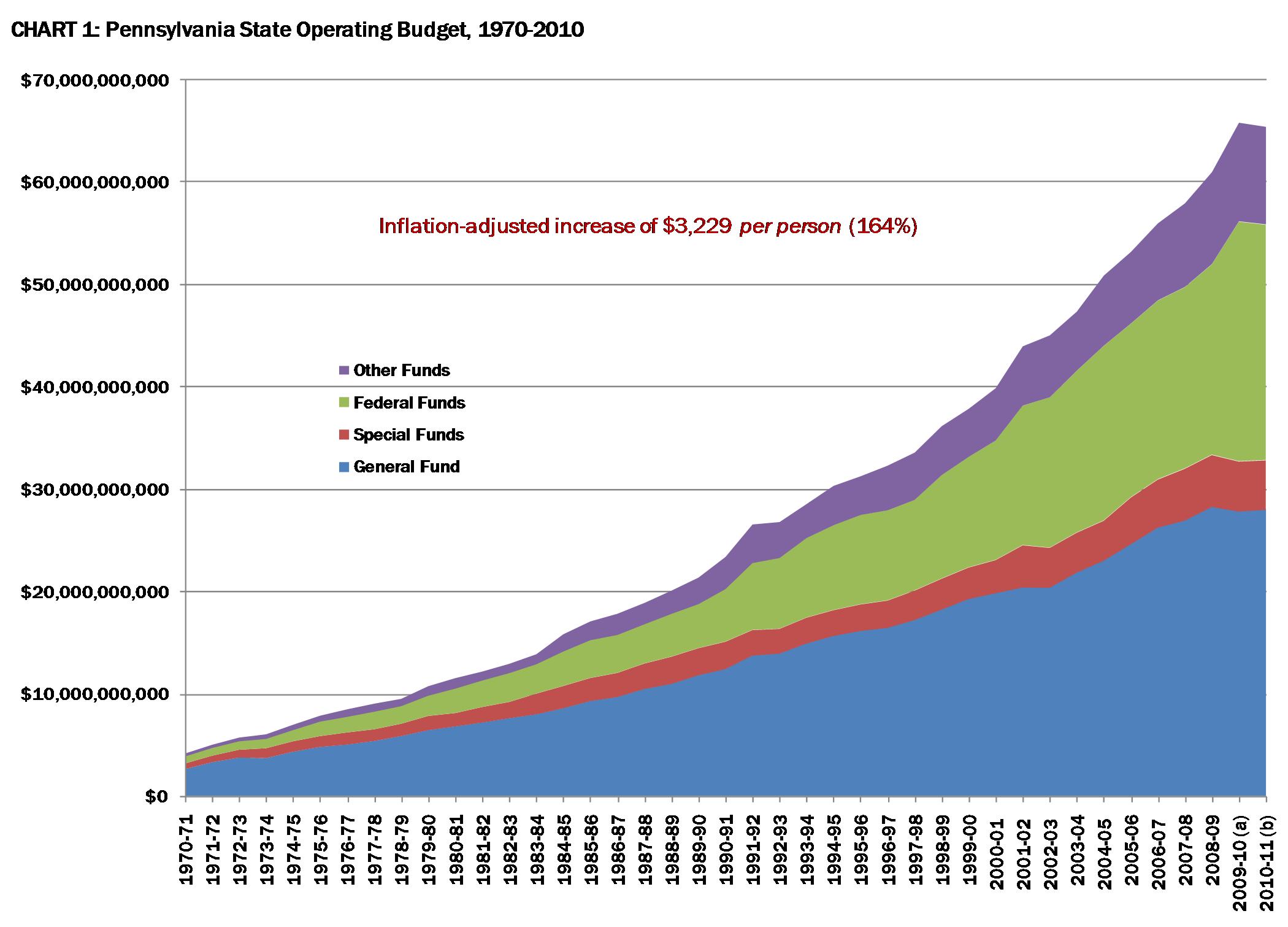

As Chart 1 illustrates, the Pennsylvania state operating budget increased from $4 billion in 1970 to more than $65 billion today. Adjusting for inflation and population growth, this represents an increase of $3,229 for every man, woman, and child in Pennsylvania. Under Gov. Ed Rendell, total operating spending grew almost $21 billion (from about $45 billion in FY 2002-03)—a 45% increase, or more than double the rate of inflation.

As the chart also reveals, the fastest growing aspects of state spending are in “other funds” and federal funds. In 1970, 62% of state spending was from the General Fund. This declined to 53% by 1990, and today the General Fund represents only 43% of the total state operating budget.

Much of this shifting has been deliberate. For example, Act 44 of 2007 created the Public Transportation Trust Fund, which took a portion of the states sales tax to give approximately $400 million in subsidies to mass transit agencies. Both this revenue and spending was previously part of the state’s General Fund. Thus, the shift would appear on paper to reduce General Fund spending, but neither spending nor taxes were lowered—this shift simply had the effect of moving tax money to a different spending account.

Additionally, the growth in federal grants to the state has not reduced the burden on state taxpayers. For starters, Pennsylvania residents also pay federal taxes, so any increase in federal spending is being borne by higher taxes (or higher debt, leading to higher future taxes) on residents of the state. Moreover, federal spending is not “free money” even to state government. Economists with the Mercatus Center find that every dollar in federal aid results in a 40-cent increase in future state and local taxes, as programs continue or expand, even after federal aid ends.5

State spending has also grown faster than personal income over the past 40 years. In 1970, the total operating budget represented 8.8% of Pennsylvanians’ personal income. This year, the spending represents an estimated 13.1% of state income.6

Capital Budget and State Agencies

Separate from the operating budget is the capital budget, which allows the state to authorize borrowing through bond issues to fund capital projects. This taxpayer-financed debt is used for construction and renovation projects such as new buildings, road construction and repair, and bridge projects. The capital budget for FY 2010-11 allows $1.8 billion in new bond issues.7

Included in the capital budget is the Redevelopment Assistance Capital Program (abbreviated RACP, but pronounced R-Cap); however these grants are not true capital expenditures. RACP has become a means to use taxpayer-financed debt for “economic development” subsidies. Since the program’s creation in 1986, the RACP debt limit has increased from $400 million to more than $4 billion today. This growth in debt isn’t used solely to support infrastructure, but to support projects that would normally be left to the private sector to fund rather than the taxpayers.

Finally, the operating budget does not include spending by independent state agencies such as the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission, the Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Agency, and the Housing Finance Agency.

Debt and Bonds

Today, Pennsylvanians owe $125 billion in state and local government debt. This equates to more than $10,000 for every person, and more than $40,000 for the average family of four in the commonwealth.

State Debt

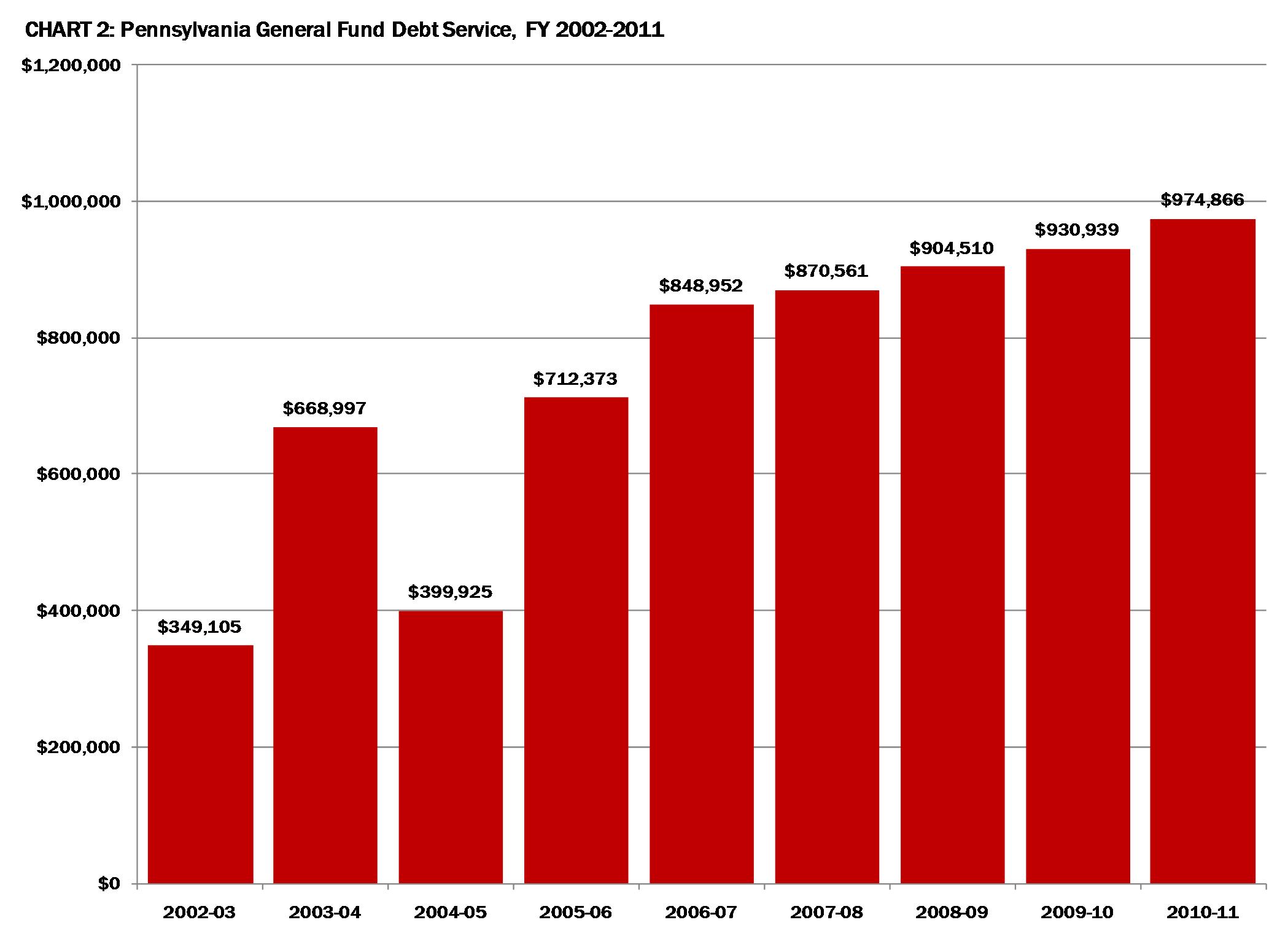

From 2002 through 2010, total outstanding state general obligation debt increased 39%, from $6.8 billion to $10.4 billion.8 Annual debt service (payments on general obligation bonds and interest) increased from $349 million in FY 2002-03 to $975 million in the FY 2010-11 budget, an increase of 180% in annual debt payments in eight years. See Chart 2 below.

This debt burden continues to grow, as $1.6 billion in new bond issues were authorized for FY 2010-11. Voter-approved bonds will add more than $200 million this year, for a total of $1.8 billion in new debt for the current fiscal year.

The major categories of state debt are buildings and structures, transportation assistance, bridge projects, and the RACP that allows the state to make grants for private projects like sports stadiums and corporate headquarters. Voter-approved bonds include Growing Greener (environmental-related projects), water and sewer bonds, and Persian Gulf veterans compensation.

State Agencies & Authorities Debt

Three-fourths of Pennsylvania’s state-level debt is in 13 off-budget state agencies and authorities. This debt, which is not reflected in state’s general obligation debt, increased from $16.8 billion in 2002 to nearly $32.5 billion in 2009—an increase of 93%.9

Among the agencies with the largest debt are the Pennsylvania Higher Education Assistance Authority, the Pennsylvania Housing Finance Agency, and the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission. These agencies have their own sources of revenues—fees, interest on loans, and charges for services.

This debt is not considered a legal obligation of the commonwealth, but in many cases is implicitly or explicitly backed by the taxpayers of the state. For instance, with Act 44 of 2007, the Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission began issuing debt to make annual payments to the state for road, bridge, and mass transit spending; this debt is backed by the Motor License Fund, i.e., gasoline taxes. The Commonwealth Financing Authority has a contract with the state Department of Community and Economic Development and receives payments ($78.5 million in 2010-11) through a line item in the budget.

Total Pennsylvania debt for the state, state agencies, and state authorities increased from $23.65 billion to over $42.94 billion over the last eight years—representing a total state-level debt increase of 82%, as shown in Table 1.

| TABLE 1: Pennsylvania State, State Agencies & Authorities Debt | ||||

| Debtor | Debt Outstanding 2002 | Debt Outstanding 2010 | Increase | Change |

| State | $6,805,184,000 | $10,451,941,000 | $3,646,757,000 | 54% |

| State Agencies & Authorities | $16,848,800,000 | $32,495,200,000 | $15,646,400,000 | 93% |

| Total State | $23,653,984,000 | $42,947,141,000 | $19,293,157,000 | 82% |

| Sources: Commonwealth of PA, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report, June 2010 ((http://www.budget.state.pa.us); Governor’s Executive Budget (http://www.budget.state.pa.us) December 2009 data) | ||||

Local Government Debt

Through the end of the 2009 academic year, Pennsylvania school districts (including career, technical, and charter schools) held just more than $26 billion in debt, according to the Pennsylvania Department of Education. This represents an increase of 35% from the $19.3 billion held in 2002.10

During the 2008-09 school year, school districts borrowed approximately $4.7 billion, while paying off $3.9 billion in interest and principle on prior debt. This pattern has been consistent, as school districts have borrowed between $4 and $5 billion, and paid off $2.9 to $3.9 billion each of the past five years.11

Other local government debt represents more than 40% of all taxpayer debt in the Commonwealth. According to the U.S. Census Bureau’s most recent data12 (2008) and Commonwealth Foundation projections, county, municipal, township, and special district debt increased from $44.9 billion in 2002 to $56.5 billion in 2010—an increase of 26%. Between 2002 and 2009, total local government debt increased by 28% from $64.29 billion to $82.6 billion, as shown in Table 2.

| TABLE 2: Pennsylvania School District, County, Municipal, Township, Special District Debt | ||||

| Debtor | Debt Outstanding 2002 | Debt Outstanding 2009 | Increase | Change |

| School Districts | $19,351,014,152 | $26,059,284,754 | $6,708,270,602 | 35% |

| County/Municipal/Twp/other | $44,943,251,000 | $56,542,341,702 | $11,599,090,702 | 26% |

| Total Local | $64,294,265,152 | $82,601,626,456 | $18,307,361,303 | 28% |

| Sources: PA Dept of Education (http://www.pde.state.pa.us/k12_finances/cwp/view.asp?a=3&q=89351) June 2009 data; U.S. Census Bureau (http://www.census.gov/govs/www/estimate.html) 2007 data/2009 projected by Commonwealth Foundation | ||||

Short-Term Tax Anticipation Notes

Historically, the state treasury has held a balance of more than $4 billion in the General Fund at the end of the fiscal year in order to pay upcoming bills and those incurred in the prior fiscal year. After the 2008-09 fiscal year, the “checkbook balance” was reduced to $2.4 billion (in contrast to $4.4 billion in June 2008 and $4.8 billion in June 2007). The end-of-year balance rebounded slightly to $2.9 billion in June 2010. As of January 2011, the fund balance was only $2.2 billion.13

The effect of this is that the state has cash flow problems—i.e., not enough cash on hand to pay bills. As a result, for the second time in two years, Pennsylvania is issuing tax anticipation notes (TANS)—short-term borrowing designed to pay the bills until the treasury is replenished with future tax revenue. The first issuance of TANS since 199814 was in December 2009 for $800 million at an interest rate of 1.5%.15 In October 2010, the state issued another $1 billion in TANS at an interest rate of 2.5%. Pennsylvania taxpayers must pay back the $1 billion, plus $25 million in interest, before June 30, 2011.16

Unemployment Compensation Loans

In addition to traditional bonded debt, Pennsylvania is also borrowing money to fund programs such as unemployment compensation (UC). In November 2009, the state began borrowing federal funds to cover unemployment benefit checks. Pennsylvania now owes $3.1 billion and is expected to owe $3.7 billion by the end of 2011. Only California, New York and Michigan have borrowed more.17 This year, Pennsylvania will owe more than $101 million in interest as the two-year grace period ends18 (though President Obama has proposed extending this grace period for another two years, then forcing states to increase what they collect from employers in UC taxes).

Automatic provisions in the current law increased employer taxes by $35 per worker in 2011. This tax is in addition to the regular unemployment taxes paid by employers and employees. Businesses will be furthered penalized for the state’s fiscal irresponsibility as the Federal Unemployment Tax Act (FUTA) Credit is reduced from 5.4%to 5.1%—costing employers another $21 per employee.19

The unemployment trust fund debt is not merely the symptom of a poor economy, but of an ill-structured system. Pennsylvania maintains some of the most generous unemployment benefits in the country, allowing individuals to accumulate unemployment benefits while collecting severance pay, Social Security and vacation pay. Thus, Pennsylvania ranks among the highest unemployment compensation costs in the nation despite consistently having an unemployment rate below the national average.

Unfunded Liabilities in Pensions and Retiree Health Care

Pennsylvania has two statewide pension funds for public employees—the Public School Employees Retirement System (PSERS) for public school workers and the State Employees Retirement System (SERS) for state workers, legislators, staff, and judges. As of June 30, 2010, PSERS had an unfunded liability of $31 billion. PSERS’s accrued liabilities—the present value of all benefits already earned by workers—totaled $79 billion, while the market value of assets actually invested was only $48 billion.20 As of December 2009, SERS had an unfunded liability of $11 billion, with accrued liabilities of $36 billion and a market value of investments of only $25 billion.21

These calculations assume 8% annual return on investment, and no benefit improvements for those currently working or already retired. Act 120 of 2010 temporarily delayed significant increases in taxpayer pension contributions by the state and school districts by arbitrarily settingagainst actuarially sound practices—the amount taxpayers will pay into the fund, further underfunding the plans. The new taxpayer contribution rates will not even cover the cost of new benefits earned by pension plan members for the next few years; hence the unfunded liability is expected to increase further.

According to PSERS projections, the unfunded liability will reach close to $50 billion for PSERS alone by 2020, before it begins to decrease. This unfunded liability creates many problems including: a dramatic increase in taxpayer contributions to the funds, greater risk if the funds don’t return 8% or better on investments, and even liquidity problems—having to put funds in shorter-term, lower-return investments that can be sold quickly in order to pay retirees’ pension payments.

Local governments also have pension plans for public employees. According to the latest data available, the 3,000 municipal and county pension plans in Pennsylvania—representing one out of every four pension plans in the nation—have a combined unfunded liability of approximately $7.3 billion.22

Additionally, state and local governments also have accrued liabilities for the health care of retirees, as many public employees get health care benefits after they retire (these are known as Other Post Employment Benefits, or OPEB). Under Government Accounting Standards Board directives (GASB 45), governments must account for these liabilities as they would with pension plans—but they do not have to pre-fund them. In fact, the state continues to operate on a pay-as-you-go basis, meaning they pay for retirees’ health care benefits out of current tax dollars. The estimated unfunded OPEB liabilities for the state, as of October 2009, are $15 billion.23

There have yet to be any official estimates of the total unfunded OPEB liabilities for the 500 school districts throughout Pennsylvania, nor for municipal and county governments.

Total Debt and Impact on Pennsylvania State Budget

Combined, as summarized in Table 3, Pennsylvania taxpayers owe approximately $194 billion in state and local debt and long-term obligations. This comes to $15,622 per person, or more than $62,000 for a family of four. This total does not include federal debt and liabilities or personal debt.

| TABLE 3: Pennsylvania State & Local Government Obligations | ||

| Debtor | Debt Outstanding | Per Capita |

| State Bonded Debt | $42,947,141,000 | $3,454 |

| Local Bonded Debt | $82,601,626,456 | $6,644 |

| Unemployment Compensation Fund Debt | $3,100,000,000 | $249 |

| State Tax Anticipation Notes | $1,000,000,000 | $80 |

| Unfunded State Pension Liabilities | $42,000,000,000 | $3,378 |

| Unfunded Local Pension Liabilities | $7,300,000,000 | $587 |

| Unfunded State OPEB Liabilities | $15,273,320,000 | $1,228 |

| Unfunded Local OPEB Liabilities | ???? | ?? |

| Total | $194,222,087,456 | $15,622 |

Moreover, as discussed above, debts and unfunded liabilities in each of these categories have been growing, and are expected to continue growing in the near future at an unsustainable pace.

While balancing this year’s state operating budget is considered the top issue for Gov. Tom Corbett and the state legislature, addressing the long-term fiscal imbalance cannot be postponed. The taxpayers cannot continue to assume more debt than it pays off year after year. Reforming unemployment compensation to make that fund solvent again, and reducing the growth of government spending to guarantee the commonwealth and local governments can make future pension payments, must be high on the agenda.

General Fund Revenue Collections

While some have pegged the FY 2011-12 budget shortfall as high as $5 billion, it is difficult to know precisely where this estimate comes from. Pennsylvania’s General Fund budget for FY 2010-11 is $28.04 billion. Included in this total is $2.7 billion in one-time aid from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (“stimulus”), along with approximately $30 million in transfers from other funds. Further, about $150 million in General Fund bills were paid for using other funds this year.

In 2009, the state transferred funds from the Health Care Provider Retention Account to the General Fund. Commonwealth Court subsequently ruled this transfer was illegal, and more than $800 million must be paid back. The ruling is currently under appeal, and it is yet unclear when, and how, this total would be repaid.

| TABLE 4: Estimated and Projected Revenue Collections | ||||

| FY 2007-08 | FY 2008-09 | FY 2009-10 | FY 2010-11* | |

| Revenue Collections | $27,020,193 | $24,471,147 | $24,619,782 | $25,650,721 |

| Change | -9.4% | 0.6% | 4.2% | |

| FY 2011-12 Scenarios | ||||

| Revenue Collections | $25,137,707 | $25,650,721 | $26,163,735 | |

| Projected Change | -2.0% | 0.0% | 2.0% | |

| Source: PA Department of Revenue * = projected; excludes refunds and one-time transfers | ||||

Through February 2011, the fiscal year’s revenue collections are 1.62% ahead of forecasts, which projects to $26.93 billion in final General Fund revenue. After tax refunds, this comes to approximately $25.65 billion in state revenue for FY 2011-12. Table 4 provides a range of revenue forecasts for FY 2011-12, assuming no change in tax law or transfers from other funds.24

There are limited options for transfers from other funds due to the use of the “Rainy Day Fund” and other fund excess during the last two fiscal years, though there are legislative options for moving both revenue and spending from other funds into the General Fund.

Pennsylvania’s Tax Burden and Impact of Taxes

Keystone State taxpayers paid $4,463 per capita in state and local taxes in 2008, or 10.2% of their income. According to the Tax Foundation, Pennsylvania’s state and local tax burden—taxes as a percentage of total income—has grown 5.2% since 1991.

Today, Pennsylvania has the 10th highest state and local tax burden in the nation, up from 24th in 1991.25 The average Pennsylvanian must work 103 days—nearly one-third of the year—to earn enough money just to pay his federal, state, and local tax bills.

Pennsylvania’s tax-borrow-and-spend approach has failed to revitalize the economy. Indeed, from 1970 to 2010, Pennsylvania’s rankings in job growth, personal income growth, and population growth were a dismal 47th, 46th, and 47th, respectively. Recent independent rankings of Pennsylvania’s economic and business climates mirror this lackluster performance. The state ranks 39th in state economic competitiveness according to the Beacon Hill Institute “State Economic Competitiveness Index,” and Forbes rates Pennsylvania as the 41st “best state for business.” The Keystone State also scored 46th in economic performance on the American Legislative Exchange Council’s Rich States, Poor States.26

This trend also shows in residents fleeing to states with lower taxes, less regulation, and greater job growth. From 1993 to 2008, the state lost a net 196,000 taxpayers (tax returns) who moved to other states in the nation, according to IRS data.27 The net loss in personal income these taxpayers took elsewhere was $10.1 billion. During Gov. Ed Rendell’s tenure (2003-2008), Pennsylvania saw a net loss of 38,000 taxpayers and $2.1 billion in income. According to U.S. Census data, Pennsylvania ranked 16th in most net residents moving to other states from 2000-2009.28

Conclusion

Pennsylvania’s budgetary challenges are rooted in the growth of state spending—not a lack of tax revenues. If General Fund spending had been limited to inflation plus population growth since FY 2002-03, spending this year would be $25.6 billion (this total includes the Public Transportation Trust Fund, discussed above). At this spending level, even without federal stimulus funds, Pennsylvania would have a $400 million surplus this year.

Likewise, increased borrowing, ongoing deficits in unemployment compensation, and deferral of payments for pensions and health care costs along with investment losses have left taxpayers with significant long-term fiscal challenges. Pennsylvania taxpayers already face one of the highest tax burdens in the nation, which has undermined economic growth.

Building a reality-based budget requires legislators to first understand the causes of Pennsylvania’s fiscal challenges—years of overspending. Only then can they begin to confront and solve our public policy problems while also respecting the lives, liberty, and property of the taxpayers who fund the state’s $65 billion annual operating budget.

Endnotes

1. House Appropriations Committee (D), “Enacted Budget: General Appropriations Act (HB 2279, PN 4032, Act 1A of 2010) Spreadsheet – June 30, 2010,” www.hacd.net.

2. Pennsylvania Office of the Budget, “2010-11 Governor’s Executive Budget,” www.budget.state.pa.us.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Sobel, Russell S. and George W. Crawley, Do Intergovernmental Grants Create Ratchets in State and Local Taxes?, Mercatus Center, August 2010, www.mercatus.org.

6. U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, “State Personal Income and Employment,” www.bea.gov; Pennsylvania Governor’s Office of the Budget, www.budget.state.pa.us.

7. Pennsylvania Office of the Budget, “2010-11 Governor’s Executive Budget,” www.budget.state.pa.us.

8. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report for Fiscal Year Ending June 30, 2010, Office of the Budget, www.budget.state.pa.us.

9. Pennsylvania Office of the Budget, “2010-11 Governor’s Executive Budget,” www.budget.state.pa.us.

10. Pennsylvania Department of Education, “Summaries of Annual Financial Report Data” http://www.pde.state.pa.us

11. Ibid.

12. U.S. Census Bureau, “State & Local Government Finances”, www.census.gov/govs.

13. Pennsylvania Treasury Department, data supplied upon request.

14. IssuesPA, “Monitoring: Commonwealth’s Use of Tax Anticipation Notes (TANS),” http://issuespa.org/content/monitoring-commonwealths-use-tax-anticipation-notes-tans

15. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Tax Anticipation Notes 2010-11, October 5, 2010, http://www.portal.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/document/993179/final_os_to_printer_pdf

16. Commonwealth of Pennsylvania Tax Anticipation Notes 2009-10, December 22, 2009, http://www.portal.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/document/738344/final_os_jan_09_pdf

17. ProPublica, “Unemployment Insurance Tracker,” www.propublica.org.

18. Andren, Kari, “Businesses on the hook to pay U.S. for unemployment benefits,” Patriot-News, January 31, 2011, www.pennlive.com.

19. Deyo, Darwyyn, “Pennsylvania Unemployment Compensation Debt Unaddressed by Rendell Administration,” Pennsylvania Independent, December 10, 2010, www.PAIndy.com.

20. Public School Employees Retirement System Commission, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report http://www.psers.state.pa.us/Publications/cafr/cafr10/FINAL%20CAFR%20Report%2020101207.pdf. PSERS uses an “actuarial value of assets”, rather than a current market value of assets, in its official reports. The actuarial value, following Act 120 of 2010, uses the 10-year average of the market value.

21. State Employee Retirement System Commission, Comprehensive Annual Financial Report,” http://www.portal.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt?open=514&objID=701628&mode=2. SERS uses an “actuarial value of assets,” rather than a current market value of assets, in its official reports. The actuarial value is the 5-year average of the market value.

22. Pennsylvania Public Employee Retirement Commission, Status Report on Local Government Pension Plans, http://www.portal.state.pa.us/portal/server.pt/document/1038662/final_2010_status_report_-_color_version_for_internet_pdf.

23. Pennsylvania Office of the Budget, “Actuarial Valuation of the Commonwealth’s Post-Retirement Medical Plan,” October 2009, http://www.budget.state.pa.us

24. Pennsylvania Department of Revenue, “Monthly Revenue Reports,” http://www.revenue.state.pa.us.

25. Tax Foundation, State and Local Tax Burdens, www.taxfoundation.org.

26. Tax Foundation 2011 Business Tax Climate Index, www.taxfoundation.org; The Beacon Hill Institute, State Economic Competitiveness Index, www.beaconhill.org; Pacific Research Institute, Index of Economic Freedom, liberty.pacificresearch.org; Forbes, “The Best States for Business”, www.forbes.com; American Legislative Exchange Council: Rich States, Poor States 3rd Edition, www.alec.org.

27. Tax Foundation State to State Migration Data, www.taxfoundation.org.

28. U.S. Census Bureau, Components of Population Change, www.census.gov.