Backgrounder

How to Balance the Budget: Revenue Options

Key Points

- Business shutdowns and their lingering effects may wipe away $5 billion in previously expected revenue growth.

- Pennsylvania’s partial-year budget to fund the government through November relied on federal emergency aid to patch a prospective deficit. The state cannot count on such extra resources in the future.

- Gambling expansion and marijuana legalization measures have been proposed to raise revenue. The dollar amounts involved are not large enough to make a difference.

- The best possible revenue measure is to fully restart private business activity and promote long-term growth through regulatory and tax reform.

- Privatization of the state liquor monopoly and the Pennsylvania Turnpike would raise significant funds while reducing the state’s liabilities.

The Budget Situation

Pennsylvania government revenue fell sharply in the spring and early summer due to government-ordered business shutdowns. The Independent Fiscal Office (IFO) reports that fiscal year (FY) 2019–20 collections in the general fund were $32 billion, 10% less than the midyear projection. IFO does project revenue will recover to $35.9 billion in 2020–21, inclusive of a shifting effect from delayed tax payments.[1] However, this will still leave combined 2019–20 and 2020–21 revenue $5 billion short of precrisis projections. Put more simply, business shutdowns and their lingering effect may wipe away two years’ worth of previously expected state revenue growth.

Expenditures, meanwhile, have increased. The latest enacted budget is an unusual partial-year budget that funds most items other than education and universities for five months instead of twelve.[2] In it, spending increases for at least 100 line items relative to the comparable prior period.[3] Moreover, Pennsylvania was in an unbalanced fiscal position even before the pandemic. Over the past five fiscal years, the total operating budget had grown by more than 5% per year while tax revenue was growing at less than 4%. Growth of nontax receipts and, crucially, federal funds filled the gap (Figure 1).

Figure 1

The new partial-year budget continued this dependence on nongeneral fund revenue and federal funds: three dollars out of every eight came from emergency aid under the federal CARES Act. The CARES Act stipulates that aid may not be used to replace lost tax revenue, but Pennsylvania’s government did exactly that in several instances, for example, in spending for various health and welfare items.[4] As of this writing, the U.S. Congress is wrangling over a prospective follow-up aid package, but the federal government will not backstop the states forever. This memo considers revenue-raising options to help Pennsylvania balance its books without help from Washington. Commonwealth Foundation’s recent report Three Steps to an Honest Budget gives an overall roadmap that also covers the expenditure side and government process reform.[5]

Sin Taxes Are No Salvation

When budgets are tight, it has historically been tempting for politicians to expand sin taxes. Sin taxes target popular but unhealthy activities like drinking, smoking, gambling, and, increasingly, the purchase of unhealthy food. Pennsylvania already relies heavily on such taxes. According to the Pew Charitable Trusts, Pennsylvania is the fourth-most-reliant state on special sales taxes, drawing 24% of its tax revenue from that source compared with 15% for all fifty states, on average.[6] The latest measures to expand sin revenue in Pennsylvania include Governor Tom Wolf’s proposal to legalize recreational marijuana and Republican senators’ circulation of a draft gambling expansion bill. Neither measure can raise revenue in an amount sufficient to solve Pennsylvania’s structural fiscal imbalance (Figure 2). The marijuana and gambling proposals also have numerous weaknesses and side effects. The sections below explain these problems and then suggest some better alternatives.

Figure 2

Marijuana Taxes Raise Little Revenue

Legalization and taxation of marijuana are properly understood as methods of drug control, not of fiscal policy. In the experience of other states, much of the money raised from marijuana legalization is spent on marijuana-related items. Specifically, California allocated about two-thirds of FY 2019 marijuana collections to the marijuana regulatory apparatus and to drug-treatment programs. A study from the Tax Foundation on recreational marijuana reached a similar conclusion in stating that, “An excise tax on recreational marijuana should target the externality and raise sufficient revenue to fund marijuana-related spending while simultaneously outcompeting illicit operators. Excise taxes should not be implemented in an effort to raise general fund revenue [emphasis added].”[7]

As it stands, legal recreational marijuana sales are ongoing in nine states. Tax rates range from as high as 37% of retail price (Washington state) down to 10% (Michigan). Six states tax the product at multiple levels (wholesale and retail) or vary taxation based on product or potency. Most states impose their taxes in addition to the regular state sales tax.

It isn’t clear how much marijuana activity is being pulled into the legal market by these measures. In California, for example, the Tax Foundation report estimates that the illegal market still accounts for 74% of sales and cites the trade publication Marijuana Business Daily in stating that total market demand is $60 billion per year compared with the legal recreational market size of $13 billion. On the other hand, the Colorado Department of Revenue commissioned a study that found that the illegal market in the state has been wholly absorbed.

Two comparables for estimating marijuana revenue in Pennsylvania are Michigan and Illinois, which have similar populations.[8] Both states legalized recreational marijuana in the past year. Based on monthly tax collections, they are earning an annualized income of $120 million and $137 million, respectively.[9] Auditor General Eugene DePasquale’s 2018 estimate that Pennsylvania can earn $581 million is clearly far off base.[10] A more realistic estimate of $120 million, even if this money weren’t used to fund marijuana-related administration, would be only 0.1% of the total state budget, or less than one day of operations.[11]

In his September 3 statement in support of marijuana legalization, Gov. Wolf pitched legalization as benefitting poor urban communities. Legalization is unlikely to do any such thing. Legalization of marijuana will necessitate licensing dealers, as in Colorado and Washington, and it is the politically connected, not the urban poor, who are the ones who stand to profit. Additionally, Gov. Wolf leaves unstated his plan for what to do if marijuana is someday legalized at the federal level. Will he bar out-of-state deliveries and restrict licensure to preserve the government’s revenue stream and protect incumbent dealers? The question is not hypothetical: Pennsylvania has been doing something similar with alcohol for almost ninety years.[12]

Gambling Taxation: False Promises and Cronyism

Discussions are ongoing in the state capitol to license video gambling in bars and taverns, tax it at 42%, and, at some later date, provide property tax relief.[13] There are no firm revenue estimates as of this writing, but even an optimistic number would be less than $350 million per year. Pennsylvania’s gambling market is already saturated, and gambling in bars is ubiquitous but not licensed. Similar to marijuana legalization, the small amount of new state revenue suggests this should be seen as a regulatory change, not a source of new revenue.

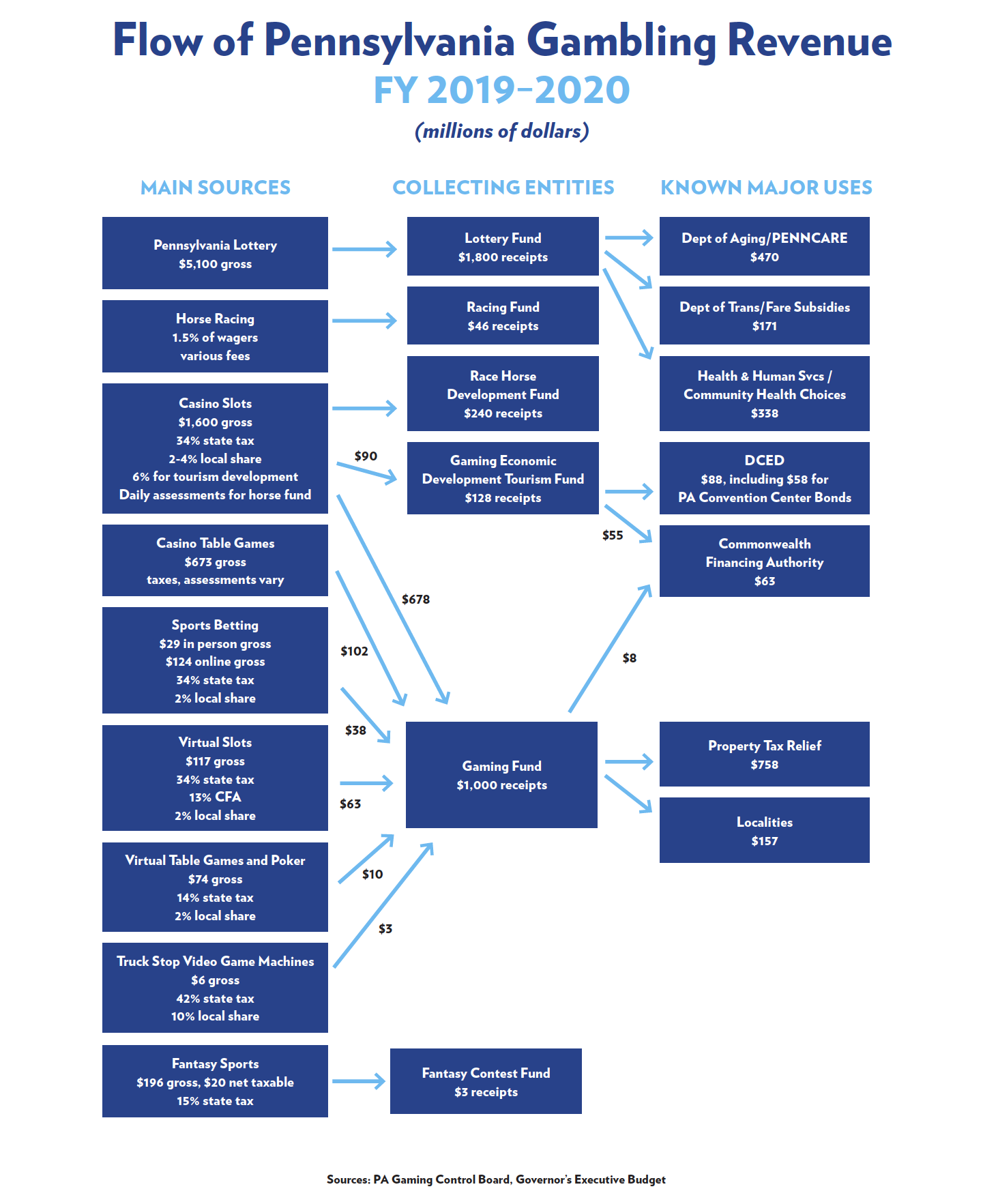

In addition, property tax relief is a false promise. The commonwealth introduced gambling licensure and taxation in 2004 after Governor Ed Rendell campaigned on the idea of using gambling revenue to reduce property taxes. Today, Pennsylvania is America’s largest casino market ($3.3 billion gross) outside of Nevada,[14] and property taxes in most localities are unchanged: the average millage rate across Pennsylvania’s 500-plus school districts is the same as 10 years ago, according to the Pennsylvania Department of Education.[15] The Case-Shiller national home price index increased by about 50% since Rendell’s first term. This means, even allowing for assessment lags, that Pennsylvanians are paying significantly more property taxes than they did before licensed gambling.[16] The State Gaming Fund did pay out $750 million in targeted property tax relief in FY 2019–2020, but this was only one dollar in every five gambling dollars collected by the state (see appendix). Rendell promised $1 billion of relief 16 years ago.[17]

Pennsylvania today has casino gambling in driving distance from every population center, as well as internet gambling, horse racing, sports betting, lottery and fantasy sports. The abundance of choice suggests there is little government revenue to be had from selling more licenses. Indeed, incumbent casino operators like Wyomissing-based Penn National Gaming opposed past rounds of casino expansion on the grounds that it reduces their market share.[18] The State Lottery Fund, which directs its net revenue to services for the elderly, has come under financial pressure as revenue from televised games like keno has not lived up to expectations.[19]

In this case, expanded gambling licensure aims not to increase consumer choice or competition, but to restrict it. It is targeted squarely at the unlicensed video games popular in some bars and billed by their manufacturers as “games of skill.”[20] The skill element is, of course, trivial, but so is the individual bet size. The games operate inside of legal, taxpaying establishments, and they are a five- to six-figure revenue source for some businesses,[21] which is significant in a year when shutdown orders have ruined so many.

The recent fortunes of small food and drink venues contrast starkly with those of corporate casinos: a majority of Penn National properties re0pened months ago, and the company’s stock is at an all-time high. Gaming corporations are large donors to lawmakers like state senate president pro tempore Joe Scarnati, and they recently threw a lavish event for him in Las Vegas.[22] Proposals to regulate small-time gambling in small establishments should aim to benefit those establishments, not their rivals.

The Best Way to Raise Revenue Is to Promote Economic Growth

The sin taxes reviewed above are unlikely to fill this year’s budget gap or future deficits. Fortunately, there is a way for the state to earn more revenue without political favoritism, new taxes, or new administrative costs: reopen the economy and let it grow.

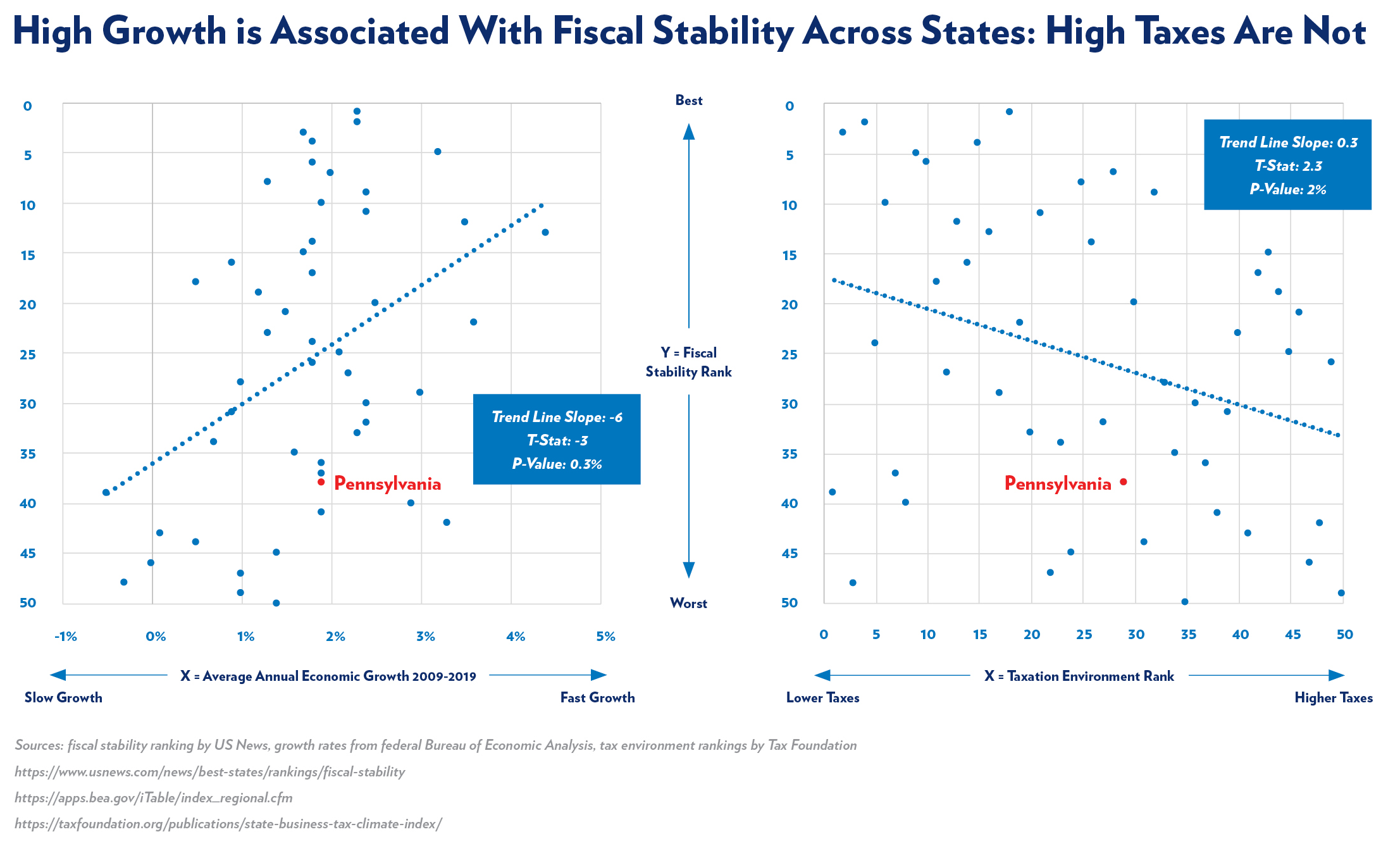

In the United States, states with the best growth rates over the last 10 years are also the most fiscally stable (Figure 3). This makes sense: states draw their most of their revenue from some combination of income and sales tax, so more private business activity means more tax revenue. In contrast, the states with the highest taxes are not the most stable. The size of the economy, not the tax regime, determines government revenue over the long term.

Figure 3

Because government revenue comes from private business activity, all of the following can be considered revenue-boosting measures:

- Liability Protection: Not all of the unpleasantness and inconvenience of visiting a business in the coronavirus era—mask rules, plexiglass at the cashier, etc.—are government mandates. Many are implemented voluntarily by businesess for fear of frivolous lawsuits. This crisis atmosphere will persist far longer than the pandemic until lawyers, not doctors, advise businesses it is safe to normalize. Liability protection bills have been introduced in the legislature as SB 1181 (Brooks) and HB 2384 (Keefer).

- Regulatory relief: New businesses open in places where they can hire and operate most easily. Pennsylvania ranks 35th in the U.S. News and World Report ranking of state business environments and 27th in a similar Forbes list (40th for growth prospects).[23] If these rankings are accurate, Pennsylvania has little chance of growing faster than its neighbors under the status quo. Legislators have proposed several fixes:

- HB 430 (Benninghoff) would allow the General Assembly to repeal regulations through a concurrent resolution. This is an important reassertion of the legislature’s constitutional dominance over appointed administrators.

- HB 806 (Keefer) would require the General Assembly to approve any economically significant regulation, defined as one with an impact of $1 million or more per year.

- HB 509 (Rothman) would create an online tracking system for state permits to make the application process simpler.

- HB 1055 (Klunk) and SB 251 (Phillips-Hill) would create an Office of the Repealer to review and amend regulations.

- SB 5 (DiSanto) would create an Independent Regulatory Review Commission and require that economically significant regulation proposals include a cost analysis for the affected private sectors.

- Operating loss deductions: Operating restrictions have already turned 2020 into a lost year for many small businesses, but they can recover more easily next year if they can use their losses to reduce their future tax liability. The state foregoes some revenue by permitting operating loss deductions, but it collects no revenue at all in perpetuity when a business closes. Incorporated businesses can already deduct operating losses. HB 1603 (Grove) and SB 202 (Ward) would permit small business to do the same.

Liquor Privatization

Economic growth is an ongoing benefit. The state can gain some one-time funds, however, by loosening the Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board (PLCB) wine and liquor distribution monopoly. Revenue gains would come from the initial privatization as well as from increased tax revenue as Pennsylvania achieves a level of liquor store density comparable to other states and residents make more major purchases locally.

The PLCB has controlled all wholesale wine and liquor distribution and also held a retail store chain monopoly since the end of Prohibition. As of 2018–19, the PLCB operated 603 retail facilities. A liquor store density report from 2017ranks Pennsylvania in line with New Mexico, a desert state, in terms of liquor stores per head.[24] If Pennsylvania had the average density of its peer states, the PLCB would operate more than 1,000 outlets. Moreover, despite its monopoly power, the PLCB was earning only a 9% profit margin as of last fiscal year.[25] The wholesale and store business is clearly more valuable in private hands, which means the state can sell it to private parties for a large profit. Liquor licenses for on-premise consumption, meanwhile, are limited to one per 3,000 residents, one of the most restrictive quotas in the country.[26] Clearly, there are more restaurants that wish to serve alcohol than can obtain licenses: the state is leaving revenue on the table.

A study conducted for the commonwealth’s department of revenue in 2011 by the consultancy Public Financial Management estimated that the sale of 3,000 to 4,000 retail licenses and 10 to 30 wholesale licenses to replace the state stores and distribution system would raise $1 billion to $1.5 billion in one-time revenue.[27]

Further revenue increases could come from the end of so-called “border bleed.” As it stands, a significant number of Pennsylvanians buy alcohol outside of the state and bring it home. This is illegal, so numbers are inexact, but a border bleed survey from 2011 indicated that about 40% of consumers mixed in-state and out-of-state alcohol purchases. [28]The sums involved are meaningful: the survey indicated that when consumers do go out of state, they spend three- and even four-figure amounts.[29] If 1% of Pennsylvania’s 13 million residents make just a $300 out-of-state purchase every year, that makes $39 million of annual taxable business activity that could have passed through a Pennsylvania store. The PFM study suggested that border bleed is many multiples of that number: 10 to 30% of all sales in the commonwealth.[30] This is not implausible considering the absence of high-end wine in most PLCB stores.

Moreover, there exists the potential of much more sales tax revenue on alcohol from an improved product mix. The PLCB remitted to the state about $542 million of sales taxes in its last reported fiscal year. Loosening the monopoly to allow more private stores, wider distribution of the most exclusive products, home wine delivery, and more restaurant licensing could boost sales tax collections by about 20%. This alone would result in a recurring revenue gain similar to that promised by marijuana legalization, with none of the attendant regulatory costs or controversy.

PLCB privatization has been introduced as HB 2457 (O’Neal).[31] It would close state stores, privatize the wholesale liquor system, and expand liquor licensure. It is similar to HB 466 of 2015, which passed in the legislature but was vetoed by the governor.[32]

Incremental liquor reforms proposed in the legislature, short of full privatization, include:

- HB 1512 (Topper) would repeal flexible pricing and reinstate the proportional pricing formula to which the PLCB was bound before it raised prices under Act 39 of 2016.

- HB 1346 (Masser) would allow businesses to purchase wine from private wholesalers.

- SB 548 (Yaw) would allow private wine and liquor stores.

These are all beneficial reforms, but only a full privatization would deliver a lump sum of cash large enough to matter for Pennsylvania’s current budget problems.

Turnpike Privatization

Easing the state liquor monopoly can be done quickly. Another major revenue measure would be to lease the Pennsylvania Turnpike to a private operator. This would be far slower and more controversial, but it could yield an upfront payment of more than $10 billion. This would be no windfall, unfortunately: most of the money would have to repay bond debt. The transaction would still be beneficial, however, because the turnpike’s finances are severely stressed. As of this spring, traffic had fallen by about 50% year on year.[33] A sustained economic recovery will allow the turnpike to avoid the worst possible scenarios for now, but the virus panic demonstrated clearly how the turnpike, once an asset to the commonwealth, has been transformed by mismanagement into a liability.

The turnpike has about $12.8 billion in bonds outstanding, 16 times its cash flow before interest of about $800 million. The borrowed money is long gone, funneled to state government for mass transit in Philadelphia. Interest payments are $620 million annually, meaning a traffic reduction of more than about 20% for the year will require the turnpike to draw on reserves.[34] The Turnpike Commission could increase tolls, but it already raised them in January. A driver paying cash to go from New Jersey to Ohio in a car pays $61.20. An eighteen-wheel truck pays $197.50 cash or $142.60 electronically.

The idea of leasing the turnpike is not new. In 2006, the Pennsylvania Funding and Reform Commission proposed leasing the turnpike to a private operator. At least one bid came in at $13 billion for a 75-year lease with a limit on toll hikes. State government declined to the lease road and opted instead for the Act 44 plan of 2007, which kept the turnpike under Turnpike Commission control while requiring it to make annual payments to the state. The turnpike is currently required to pay $450 million annually through 2022, at which time annual payments will fall to $50 million through 2037. The Pennsylvania Department of Transportation has been sending $250 million of that money annually to Philadelphia via the Public Transportation Trust Fund. The turnpike funds its payments to the state by borrowing and hiking tolls. Unlike the proposed lease, Act 44 placed no limit on toll increases.

Last year, after releasing a report on the Turnpike Commission, Auditor General Eugene DePasquale announced that the current situation “just isn’t sustainable” and “the idea that motorists and truckers on [the turnpike] are going to be able to pay that entire debt back is literally delusional.”

The state should not unload the turnpike for less than full value, but it would be prudent to at least solicit a valuation and test the market. If a private lessor offers a price of $1.5 billion more above the turnpike’s onerous debt load, it may be a good trade for the taxpayer. A recent study by the Reason Foundation suggests an even more generous valuation for the turnpike: $16 billion to $25 billion. This figure could serve as a starting point for further inquiry.[35]

Appendix

[1] About $2 billion less tax revenue was collected in FY 2019–20, and about $2 billion more will be collected in 2020–21 because the 2019–20 tax filing deadline was delayed. Latest revenue projections as of this writing are from Official Revenue Estimate FY 2020-21. Pennsylvania Independent Fiscal Office report, June 22, 2020, http://www.ifo.state.pa.us/releases/type/6/Revenue-Estimates/.

[2] July through November 2021, that is, the first five months of FY 2020–21.

[3] A line item budget from the House Appropriations Committee is viewable at https://tinyurl.com/PAbudgetworksheet.

[4] Strange Budget for Strange Times: 2020-2021 Budget Overview, Commonwealth Foundation, June 22, 2020, https://www.commonwealthfoundation.org/policyblog/detail/strange-budget-for-strange-times-2020-2021-state-budget-overview.

[5] “Three Steps to an Honest Budget,” Commonwealth Foundation, February 16, 2020, https://www.commonwealthfoundation.org/policyblog/detail/three-steps-to-an-honest-budget-fiscal-reform-priorities-2020-2021.

[6] “How States Raise Their Tax Dollars, FY 2019,” Pew Charitable Trusts, https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/data-visualizations/2020/how-states-raise-their-tax-dollars.

[7] A Road Map to Recreational Marijuana, Tax Foundation, June 2020, https://files.taxfoundation.org/20200608144852/A-Road-Map-to-Recreational-Marijuana-Taxation.pdf.

[8] Ten million and 13 million people, respectively. The population of Pennsylvania is about 13 million.

[9] A Road Map, Tax Foundation.

[10] Press release with link to report: “Auditor General DePasquale Says State Could Reap $581 Million Annually by Regulating, Taxing Marijuana,” Office of the Auditor General, https://www.paauditor.gov/press-releases/auditor-general-depasquale-says-state-could-reap-581-million-annually-by-regulating-taxing-marijuana.

[11] State government collected and spent $86 billion from all sources, including federal, in FY 2018–2019. See Slicing State Finances Part 3: Revenue on Autopilot, Commonwealth Foundation, October 28, 2019, https://tinyurl.com/y75xbam9.

[12] “On Alcohol, Can We At Least Be Sweden?” Commonwealth Foundation Policy Blog, August 27, 2019, https://www.commonwealthfoundation.org/policyblog/detail/on-alcohol-can-we-at-least-be-like-sweden.

[13] “Pa. Senate Shaping Plan to Allow Bars, Clubs to have Slots-Like Video Gaming Terminals,” Penn Live, June 22, 2020, https://tinyurl.com/y9y2v768.

[14] State of the States Report, American Gaming Association, June 2019, https://www.americangaming.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/06/AGA-2019-State-of-the-States_FINAL.pdf.

[15] Forty-four mills, with significant variation, Pa. Department of Education website, https://www.education.pa.gov/Teachers%20-%20Administrators/School%20Finances/Finances/FinancialDataElements/Pages/default.aspx.

[16] Federal Reserve “FRED” Economic Database, https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/csushpinsa.

[17] “Pennsylvania Governor Signs Bill to Bring in 61,000 Slot Machines,” Associated Press, July 5, 2004, https://tinyurl.com/y4p2q4c7.

[18] Channel 69 News, Berks County: “Penn National Weighing Legal Options Over Gambling Expansion,” https://tinyurl.com/penngamingstatement.

[19] “Older Pennsylvanians Lose from Lawmaker’s Raid on Lottery Fund,” Penn Live, January 13, 2017, https://tinyurl.com/y3zh42v5.

[20] “Unregulated Gambling Finds a Corner at the Corner Store (Among Other Places),” Penn Live, June 12, 2018, https://tinyurl.com/y5k666z4.

[21] “Video gaming machines in Pa. bars? Not so fast,” Philadelphia Inquirer, September 18, 2017, https://tinyurl.com/yy2fnk6d.

[22] “Top Pa. GOP Lawmaker Fast-Tracking a Lucrative Gambling Expansion That Would Benefit a Major Campaign Donor,” Spotlight PA, June 19, 2020, https://tinyurl.com/y83jk4km.

[23] “Business Environment Rankings: Which States Are Booming With New Ideas,” U.S. News & World Report, https://www.usnews.com/news/best-states/rankings/economy/business-environment. See also “Best States for Business,” Forbes, https://www.forbes.com/best-states-for-business/list/#tab:overall.

[24] See http://thecapitolist.com/wp-content/uploads/2017/04/Liquor-Stores-in-Non-Quota-Non-Control-States.pdf.

[25] Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board, unaudited financial report, https://www.lcb.pa.gov/About-Us/News-and-Reports/Pages/Financial-Reports.aspx.

[26] Pennsylvania Liquor Control Board website, https://www.lcb.pa.gov/Licensing/Topics-of-Interest/Pages/Quota-System.aspx.

[27] Liquor Privatization: Final Report, PFM Group, for Pennsylvania Office of the Budget, October 3, 2011, https://www.commonwealthfoundation.org/docLib/20200919_PFMReport2011.pdf.

[28] 2011 PLCB Border Bleed Tracking Study, Neiman Group, p. 12, https://www.commonwealthfoundation.org/docLib/20110912_PLCB_BorderBleed.pdf.

[29] Ibid., p. 121.

[30] Ibid., p. 9.

[31] Pennsylvania State Legislature website, https://tinyurl.com/y2kyb2zq.

[32] See https://www.legis.state.pa.us/cfdocs/billInfo/billInfo.cfm?sYear=2015&sInd=0&body=h&type=b&bn=466.

[33] Testimony of Pennsylvania Turnpike Commission CEO Mark Compton to the Pennsylvania Senate Labor and Industry and Transportation Committee, June 15, 2020, https://www.paturnpike.com/pdfs/about/covid19/Testimony_House_Transportation.pdf.

AQ: Footnote 34 text is missing.

[35] Robert Poole, “Why Governments Should Lease Their Toll Roads,” Reason, August 25, 2020, https://reason.org/policy-study/should-governments-lease-their-toll-roads/?utm_medium=email.