Media

School Choice: Stuck in the Middle (Class)

“I fear we’ve become a school for the haves and the have-nots,” one private school leader in Florida worried. What’s happened to those in between? The wealthy can afford to send their children to a private school. Meanwhile, income-based school choice programs, such as tax credit scholarships and vouchers, have helped low-income families access educational options.

Unfortunately, folks in the middle—we might call them the “have-somes”—are squeezed out of the private school market. As we celebrate National School Choice Week, it’s a good time to consider the impact of shrinking education options for middle income families.

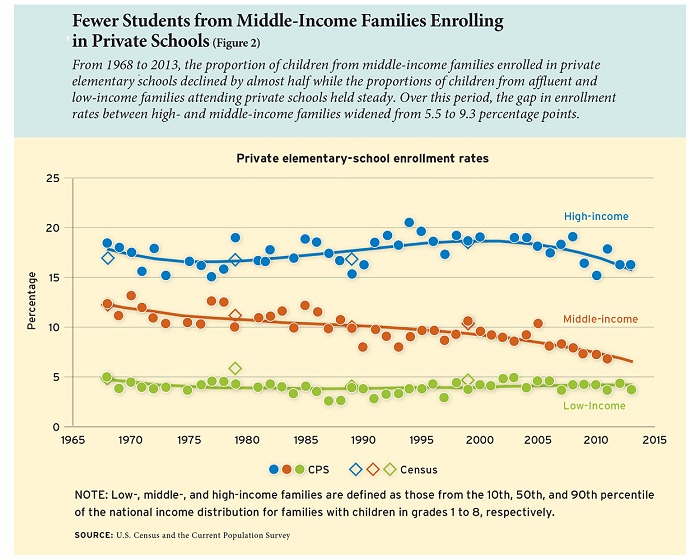

According to a recent report by Education Next, private school enrollment has been stable for upper-income families since 1968, hovering around 16-18 percent. Private school enrollment for lower income families has remained steady at around 5 percent. For middle-income families, however, there has been a noticeable decline. In 1968, 12 percent of children from middle-income families attended private school; by 2013, that number had declined by almost half, to 7 percent.

Reprinted courtesy of Education Next

This decrease in educational access for middle-income families can have wide-ranging consequences. Numerous studies have shown the positive benefits of school choice, including safer learning environments, improved academic achievement, reduced criminal activity, and decreased racial segregation. Middle-income families are increasingly denied these potential benefits due to school choice income limits.

There are other, less quantifiable impacts on communities. Equipping middle-income families with private school choice options can prevent them from fleeing urban areas when their children reach school age. According to Dr. Bartley Danielson, who studies the impact of school choice on real estate and the environment,

We know that people are leaving those areas with weaker assigned schools when their children hit school age. If you give middle-income people in those areas a way to stay many of them will, and you end up with better neighborhoods, better grocery stores, for example. … That store might employ 100 people. Not only that, poor people get to go to the grocery the same way that the rest of the community does.

This economic diversity would also impact schools themselves. Studies have shown that concentrated poverty is strongly correlated with lower educational achievement. Poorer communities have fewer two-parent families, school volunteers, and college-educated parents. Highly educated parents often have higher educational expectations for their children, which can raise the standards for their classmates as well.

As middle-income families stay in urban areas with the ability to choose the best school for their children, schools will compete to earn their trust. This will improve all schools—public and private.

Pennsylvania’s tax credit scholarship programs could help middle-income families access school choice. Unfortunately, arbitrary caps on available tax credits stifle these programs—and thousands of families are turned away each year. Moreover, businesses are discouraged from participating by political shenanigans that complicate the process.

To address the shortcomings in the tax credit scholarship programs, lawmakers should follow Florida’s lead and enact an automatic escalator for the education improvement tax credit (EITC) program. This would ensure all families who want to participate are able, provided they meet the income criteria.

Expanding the EITC is a simple way to ensure students at every income level have access to the education that fits them best.