Testimony

Approaches to Property Tax Reform

Testimony of Nathan A. Benefield to the Pennsylvania House Select Committee on Property Tax Reform

Good morning, my name is Nathan Benefield; I am the director of policy analysis for the Commonwealth Foundation, Pennsylvania’s free-market think tank based here in Harrisburg. I want to thank Chairman Quigley and the members of this select committee.

As this committee has met several times already, and since it was laid out in the resolution convening this committee, I won’t spend much time discussing the problem: Property taxes are high, have been rising and will continue to rise. Property taxes are the single largest source of state and local government tax revenue in Pennsylvania, at more than $15.5 billion, according to the latest U.S. Census data. Over the most recent 10-year period, school district property taxes alone grew 66 percent, during a period when inflation was less than 30 percent.

The questions are whether there is a better system for financing government, and how we can address the drivers of high property taxes. My testimony will provide principles for effective tax reform and provide policy solutions to solve the underlying problem—the rapid growth of property taxes.

Tax Reform

The fact is, all taxes are harmful to the economy. As the basic principle states, when you tax something, you get less of it. Now on the other hand, taxes are necessary to support the fundamental functions of government. This paradox leaves us with two questions. The first is which tax is the “least bad tax.” The second is how to minimize taxes and reduce unnecessary spending. There are five tax reform principles to ensure harm to the individual is minimized and revenues are adequate to provide necessary services.

- Taxes should be a low rate to keep Pennsylvania economically competitive.

- Taxes should be assessed over a broad base and to the extent possible, across those who benefit from services. Taxes should not be used to favor certain individuals or companies, should not distort the economy, and should not be used to tax unpopular groups.

- Tax rates should be flat, and taxes should be simple to keep compliance costs low.

- Taxes should be transparent, and taxpayers should be able to clearly identify the amount of their tax burden.

- Taxes should not cause undo harm to those who lack the ability to pay.

The property tax is a relatively good tax on a number of these grounds, including transparency. And when looking at property taxes to pay for police and fire protection, it is clearly tied to those who benefit from services.

However, property taxes can be the most harmful to those who cannot pay. Specifically, individuals can lose their homes for failing to pay property tax. This moral argument is the strongest case for eliminating property taxes, though this harm could be remedied simply by changing the law so that a homeowner will not lose their home over unpaid property taxes.

From an economic perspective, the evidence over which tax is the least harmful is mixed. There are at least a couple of recent studies suggesting high property taxes are a greater threat to state prosperity than other taxes.

In a 2011 working paper for the Mercatus Center, Antony Davies and John Pulito find that while high income tax rates drive residents to move to other states, “the effect of property taxes on migration is significantly stronger than the effect of high-income tax rates on migration.” A 2012 study completed by Arduin, Laffer & Moore Econometrics for the Texas Public Policy Foundation found that eliminating property taxes and replacing them dollar for dollar with a sales tax would increase personal income by 1.8 to 4.7 percent over a five year period compared to with the current tax structures.

Spending Reform

While working to develop the best system of taxes is critical, tax reform should be part of a more comprehensive reform package to address excessive government spending. On its own, a dollar-for-dollar tax shift would not reduce Pennsylvania’s overall tax burden, which is the 10th-highest in the country. Rather, it is equally critical to look at the spending side of the ledger.

The problem with property taxes isn’t just in the nature of the tax, but in the growth of spending, particularly by school districts, which receive the lion’s share of property tax revenue.

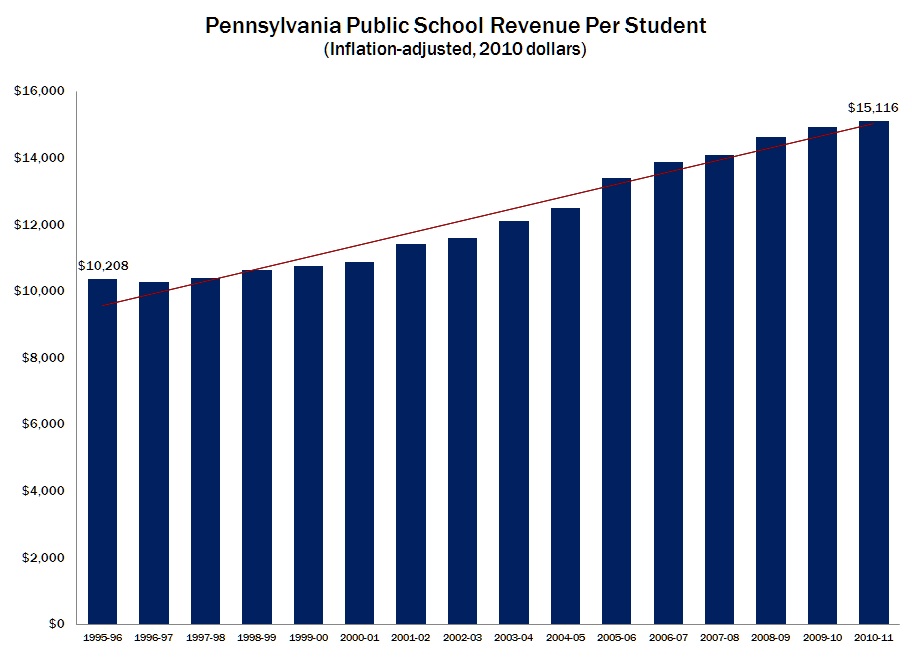

From 1995-96 to 2010-11, Pennsylvania doubled taxpayer spending on K-12 education from $13 billion to more than $26 billion. This increase is common to all revenue sources. Local school tax revenue increased by 115 percent, while state and federal subsidies to public schools grew by 97 percent. Factoring in inflation, real tax revenue per student increased from $10,000 to more than $15,000 last year.

These spending increase have done little to improve the quality of education. SAT scores have been flat and state results on the U.S. Department of Education’s Nation’s Report Card haven’t improved much since 2002. Studies of school district performance show no correlation between district spending and student achievement.

Spending increases by local governments outside of education have grown only slightly less rapidly. According to Census figures, Pennsylvania local government spending for everything outside of education increased 94 percent from 1995 to 2009.

There are number of policy changes state lawmakers can adopt to help address the spending increases which are driving local property tax increases.

Change the state school funding formula to weighted student funding. Creating a new state funding formula would answer questions about how to distribute money to school districts, and is particularly critical with any shift from local to state tax revenues. Currently, under “hold harmless,” school districts are guaranteed their previous year’s funding, plus increases based on enrollment growth, the local tax burden, and the school district’s relative wealth or poverty.

This hold harmless principle makes school districts impervious to changes in enrollment or the economy. For instance, from 2000 to 2011, public schools saw a decline in enrollment of 35,000 students, yet total staff grew by nearly 36,000. This is due in part to growing districts adding staff to meet demand, while shrinking districts had no reason to reduce spending or staff—as they received more in state subsidies and saw little change in local tax base.

Given the latest recession and economic picture, which includes a rare decline in home values, schools are facing a new fiscal reality.

Instead of funding districts based on trends of prior decades, the state funding formula to districts should be based on enrollment, weighted (i.e., providing higher levels of funding) for low-income and special needs students. As of 2009, 14 major school districts and Hawaii use weighted student funding to allocate funds to local schools.

Redefine “prevailing wage.” One of the biggest cost drivers in education spending and school taxes are mandates, including the Prevailing Wage law. While instructional costs increased by 93 percent over the last 15 years, public school spending on construction and debt grew by 158 percent. Construction and debt payments now represent almost 11 percent of total public school spending.

The prevailing wage law exacerbates these costs. County-by-county data from the Pennsylvania State Association of Boroughs shows how prevailing wage mandates raise labor costs between 30 percent and 76 percent vs. market rates across the commonwealth.

If lawmakers are looking for savings without cutting educational programs or laying off teachers or local government workers, getting rid of prevailing wage is the most effective reform they can enact. In 1997, Ohio allowed its school districts to opt out of the state’s prevailing wage mandate. The state’s Legislative Service Commission found schools saved almost $500 million as a result, for an overall savings in construction of 10.7 percent.

In 2010, Pennsylvania taxpayers spent $12.7 billion on construction (by state and local governments) that was subject to the prevailing wage law. Using county wage data, typical labor costs on construction projects, and the experience of other states that suspended or eliminated their wage mandates, that translates to about 10 to 20 percent in extra costs. Overall, that’s an additional $1.3 billion to $2.5 billion that taxpayers pay. That’s $400 to $800 more in taxes for the average family of four.

Reforms like HB 709 and HB 1191 that allow school districts and local governments to set the prevailing wage for their own construction projects would help alleviate the cost pressures driving up property taxes.

Expand school choice. Lawmakers should continue to embrace school choice, including tax credit scholarships and access to charter and cyber schools. These school choice programs spend a fraction of what school districts spend per pupil. Expanding the number of students in lower-cost schools of choice, when combined with a shift to a student funding formula, would save tax dollars and improve the quality of education.

Enact state spending limits. Government spending growth should be limited to the cost of providing services. In 1992, Colorado voters approved a constitutional amendment call the Taxpayer Bill of Rights (TABOR), which limited spending growth at both the state and local level to inflation plus population growth. This spending cap could be exceeded with approval from voters. From 1997 to 2001 Colorado refunded more than $3.2 billion in taxes to residents—nearly $3,200 per family of four.

Spending limits should restrict the growth of government spending to inflation and population growth, which does not require any cuts. In the case of school districts, spending growth could be limited to inflation plus enrollment growth. Such measures would protect Pennsylvania taxpayers from spending that grows faster than their ability to pay. A recent study by Matthew Mitchell of the Mercatus Center finds that spending and taxation limits are most effective when they are tied to inflation and population growth, and require supermajorities of state or local legislative bodies.

Moreover, limiting the growth of future spending is politically popular. In Susquehanna Polling’s Spring 2012 statewide poll, nearly two-thirds of Pennsylvania voters support limiting the growth of state government (65 percent), with fewer than one-quarter opposed. Democrats supported spending limits by a 55 to 30 margin, while more than 70 percent of Republicans and Independents support spending limits.

Current legislation to cap the growth of government spending includes HB 116 and HB 974, though neither bill currently addresses limits for local government.

Enact comprehensive pension reform. Skyrocketing pension costs threaten the solvency of many local governments across the state, and will impose far greater burdens on property taxpayers in the coming years. The Commonwealth Foundation supports a five step pension reform strategy that begins with a defined-contribution plan for all new employees—at the state, school district, and local level.

To be sure, such a reform does not reduce the unfunded liability for current employees, but will provide retirement plans that are affordable for taxpayers, predictable for state and local governments, and are paid while workers are employed rather than transferred to future generations. Additional pension reform steps will help reduce costs by curtailing unearned pension benefits, prohibiting borrowing to finance pensions, and adopting funding consistent with accounting rules.

Only after these initial reforms should lawmakers seek to provide funding to pay off unfunded pension obligations, without raising taxes or increasing debt.

Address collective bargaining reform. Restricting the benefits that are subject to collective bargaining agreements, including health care plans, would give local elected officials more control over their costs. Reforms recently enacted in Wisconsin proved controversial and were subject of union protests, but have been proven to save the state and local governments billions and prevent massive tax hikes. As noted in the Wall Street Journal last week,

A new actuarial report presented at a Milwaukee school board meeting this week shows that the district’s post-retirement benefit liability (not including pensions) has dropped by $1.4 billion, or about 50%, thanks to changes made possible by the governor’s reforms. The district estimates that raising eligibility for retiree health benefits and redesigning health plans will save $117 million this year alone.

Just giving school and municipal officials the power to find the most affordable health coverage plan for employees, rather than go through labor negotiations, could save Pennsylvania taxpayers millions in additional costs, and may even prevent future teacher strikes.

In summary, to protect Pennsylvania homeowners from burdensome property taxes, and to maintain a tax climate that keeps the Keystone State economically competitive it is necessary both to work towards tax reform, and to look to ways to control the spending which is driving tax increases.

This concludes my formal testimony. Thank you for the opportunity to testify, I look forward to any questions and discussion.